“Boo!” No, “Boobs!” As many around the country prepare to dress up in costume, politely ask for candy (isn’t “Trick or treat?” really just culturally condoned blackmail?), and yell, “Boo!”, I’m thinking that we should take a moment and instead yell “Boobs!”  It is, after all, the final moments of the Breast Cancer Awareness month of October. Although raising money to find a cure and raising awareness about the importance of early detections are 365 day/year activities, it is this month that we see NFL football players wearing pink (www.nfl.com/pink), Ford Motors hawking “Warriors In Pink” clothing in addition to cars (www.shopwarriorsinpink.com), and the memory of Susan G. Komen being bravely used to raise millions of dollars for research, education and support (www.komen.org).

It is, after all, the final moments of the Breast Cancer Awareness month of October. Although raising money to find a cure and raising awareness about the importance of early detections are 365 day/year activities, it is this month that we see NFL football players wearing pink (www.nfl.com/pink), Ford Motors hawking “Warriors In Pink” clothing in addition to cars (www.shopwarriorsinpink.com), and the memory of Susan G. Komen being bravely used to raise millions of dollars for research, education and support (www.komen.org).

This is Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and I have spent the entire month trying to tell one story. This story. A story of bravery. A story of love. A story of survival. My friend’s story.

Twenty-two years ago, my soon-to-be-friend’s mom was diagnosed with breast cancer. She delayed treatment only briefly so she could host out-of-state youth group guests, including me. As a result, I met a wonderful girl and we became friends; a friendship that remains today. After enjoying some true Midwestern hospitality, I returned to Connecticut and Rachel’s mom had a single mastectomy and then endured chemotherapy to ensure no rogue cancer cells remained in her body.

Though Rachel and I did not speak about it at the time, I now know that she understood that there was an increased risk of her one day facing cancer. In truth, most of her energy was spent being scared about her mother and the very real fear that cancer would kill her mother. Fortunately, her mom responded well, and was deemed cured after a set number of healthy years passed.

More fortunately, Rachel’s mom and her physicians remained vigilant in her post-diagnosis years. Nineteen years after her battle with cancer, Rachel’s mom was diagnosed with breast cancer a second time. (Who says life is fair?) These rogue cells required a second mastectomy. Her mom, though, was spared the unfairness of chemotherapy during the second event.

Though the exact timing is not clear to me, sometime around the second diagnosis, Rachel’s mom pursued testing to see if she was genetically predisposed to breast cancer. The math was easy, if she was negative and she was not a carrier, she could spare her two daughters from undergoing the stress of being tested and waiting for results. Rachel’s mom’s results? Positive. She was a carrier for a mutation to a BRCA gene, which is part of a class of genes known as tumor suppressors. (See http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/BRCA for more information.) What could be scarier (not in the Halloween way) than thinking you could lose your mother to breast cancer not once but twice? Perhaps, knowing that you and your sister could be at risk for the same genetic mutation….

Rachel and her older sister were tested. Both tested positive. And at that moment, my friend, Rachel, went from being the 15-year-old who once had a crush on me (Full disclosure: I once had a vested interest in her breasts.) to being my hero. She accepted the scientific news that her risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer was greatly increased. She didn’t bury her head in the proverbial sand as many people do when faced with bad medical news and tough choices. She planned her life. She worked with her husband to decide on a child-bearing strategy. This news, after all, arrived five months after their second son was born. That was five years ago.

To his credit, her physician husband joined Rachel in avoiding what seemed like shallow body image concerns (Obviously, every woman would view these issues differently, and I offer no judgment… just Rachel’s perspective) and focused on keeping his wife alive and safe. “Fear was not going to stop me from saving my own life,” Rachel recently told me while acknowledging that the positive test was horrifying.

As she faced surgery, Rachel knew that great reconstruction options existed, and unlike many women that I have met, who fairly are concerned with losing some part of what they define as their “womanhood,” Rachel was only concerned with the little people in her life. She summed up her view poignantly: “Was I worried about what my boobs would look like? No. I wanted to ensure that my kids were not orphans.” So, with that in mind, Rachel and her husband put a broad plan in place: 1. Determine how big of a family they wanted; 2. Finish having kids; and 3. Live within Rachel’s physician’s directive to have the necessary surgeries by the time she turned 35. Thirty-five??? These are decisions that no one should have to face. But, they are certainly moments that should be reserved for someone at least twice her age. Again, a hero in the making.

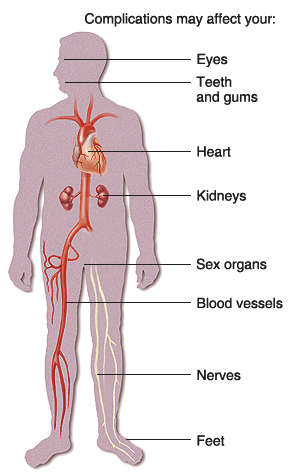

With the making babies part complete, Rachel’s ovaries were surgically removed 12 months ago. The ovaries went first because ovarian cancer is nearly impossible to detect until it reaches late stages. Even in the world of cancer, it’s an unfair disease. Without her ovaries, she has, in essence, undergone premature menopause. She had to deal with hormonal changes, a little moodiness, some mild body temperature changes, and ultimately hormone replacement therapy (“HRT”). She did so without complaint. All the while, Rachel kept life in perspective. Hot flashes (and she claims hers “weren’t so bad”) be damned. She was focusing on living. And looking back, she is grateful that her surgery had no complications. It’s only after I remind her about the “pee bag” that she laughs and drifts momentarily back to the life with a catheter. Though surgery went well, her bladder was nicked, and until it was healed, she had to wear the “pee bag” that was threaded into her urethra. Her kids would exclaim, “I can see your pee!” You have to find humor to survive life’s biggest challenges. Maybe that’s one of the silent lessons that Rachel wants to share.

Six months after surrendering her ovaries, a surgeon removed both of her breasts. Though it has been only been six months since undergoing a radical double mastectomy, Rachel is not disturbed about the changes to her body. “I don’t have nipples right now,” she admits. But, “I’m not a nude model so who is going to see them?” I think that she undersells what she’s been through. Though technology and progress has brought mastectomies to a different level, it is still a process. She woke from her first breast surgery with “expanders” in place to help prepare for the reconstruction phase that took place in July. In the end, she jokes that after four kids, her “boobs look better than ever!”

Was her decision, the right decision? For Rachel, absolutely. “Being able to be here for my kids as long as they need me… removing one thing that won’t kill me” made the tough decisions much easier. In fact, my hero friend Rachel, is inspiring about her experience. “It was empowering to take control against something like cancer.”

Rachel learned other lessons through her personal anti-cancer campaign. First, pain is bad. Second, it’s hard to be dependent on others for everything. She did have moments of feeling helpless (and ultimately “bliss when I could fold my family’s laundry for the first time.”) Third, this takes a toll on those people that love you, especially one’s children who do not totally understand what is going on with mommy. (Frustrated, her son once said, “I’m going to hit you in your surgery.”) With a very special husband, loving parents, understanding children and truly remarkable friends, Rachel survived the period when she physically could not pick up anything, when she couldn’t clean, grocery shop, drive carpool or make a meal. If it takes a village, Rachel lives in a very special Florida village.

Rachel is healthy and feeling good. Her energy flows through the phone even when we spoke on the phone today. She’s learned lessons that she should not have had to, though. She talks about an “awakening” that took place throughout the process of protecting her body. She appreciates the little things like “not being in pain, not needing pain medications, and all the little things that make life so great.” She is a mother to four wonderful children: seven, six, three, and 20 months!

Two of her kids are girls, though. They might have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. And while Rachel hopes that they won’t have to make decisions because maybe her kids will live in a cancer-free world, she hopes that they will make the right choice and be tested. “I’m not a gambler,” Rachel confides, and “I hope my girls aren’t either.” Her girls – and, in fact, all four of her children – will not have to look far to find an amazing role model. And, hero. (I know I have.)

She doesn’t know it, but I always cry when I hang up the phone with Rachel. I can’t always explain why. But, today, I cried because it is Breast Cancer Awareness Month and that 15-year-old that let me touch her boobs in her parents’ basement so many years ago now has the most grown-up message for women: “Be aware. Be strong. Take charge. Know your risks and do something about it.”

There are still things to be scared about. Rachel’s sister, as mentioned above, tested positive for a mutated gene. She’s older, just welcomed another child to the world, and does not seem to have a plan in place to avoid the horrors of cancer. I don’t blame her. But, I do join Rachel in worrying about her. But then again, I wear a pink ribbon my heart every day because I worry about all the women and girls in my life. As October comes to an end, I hope you’ll think of Rachel’s bravery, and the moms/sisters/aunts/daughters/grandmothers in your life, and make sure that we continue to fight cancer – breast, ovarian and all others – so that our children read about the terrible disease only in history books.

Special thanks to my dear friend, Rachel, for letting me share her story.

It is, after all, the final moments of the Breast Cancer Awareness month of October. Although raising money to find a cure and raising awareness about the importance of early detections are 365 day/year activities, it is this month that we see NFL football players wearing pink (

It is, after all, the final moments of the Breast Cancer Awareness month of October. Although raising money to find a cure and raising awareness about the importance of early detections are 365 day/year activities, it is this month that we see NFL football players wearing pink (